HISTORY

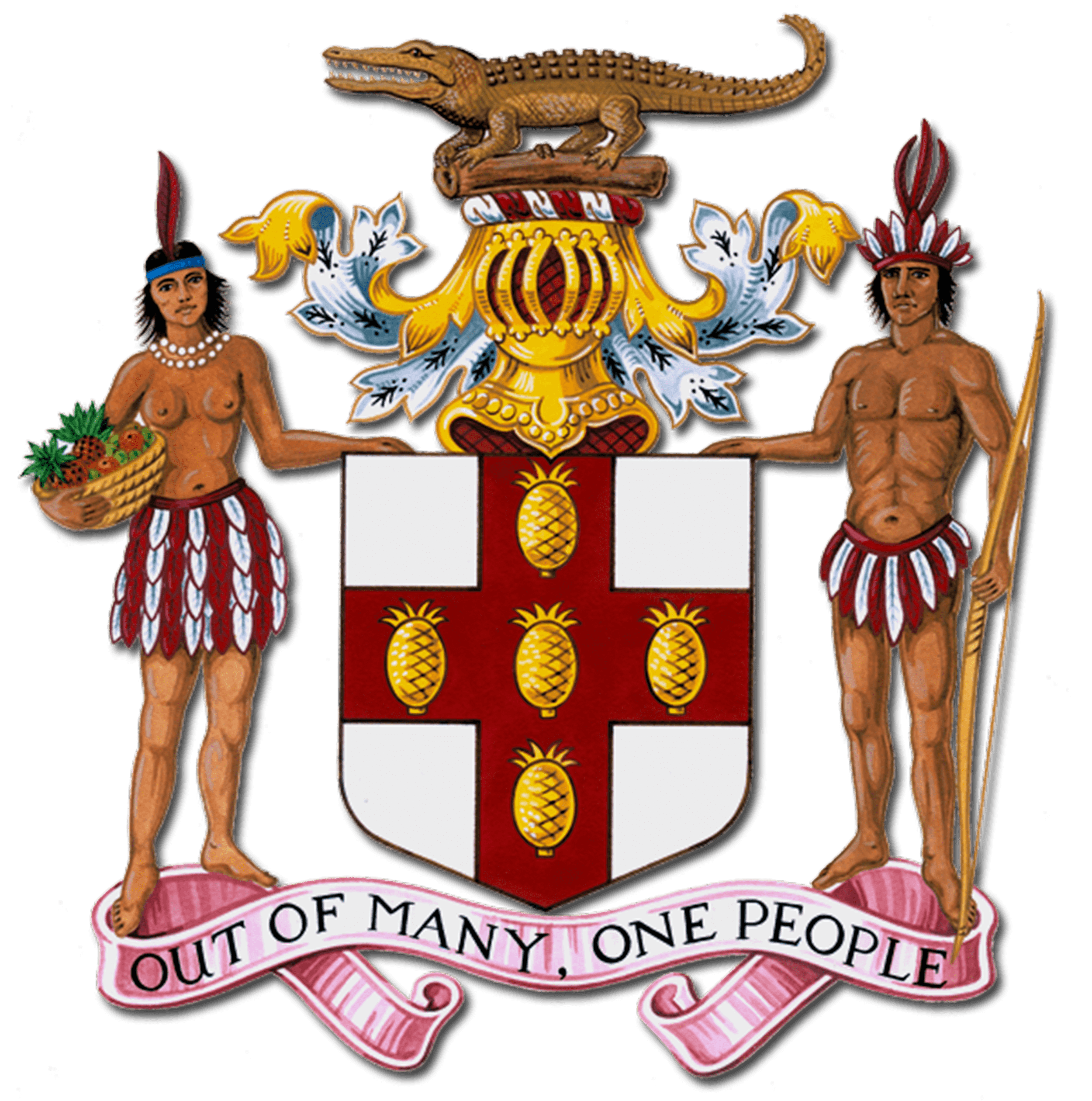

The Caribbean Island of Jamaica was initially inhabited in approximately 600 AD or 650 AD by the Redware

people, often associated with redware pottery. By roughly 800 AD, a second wave of inhabitants occurred

by the Arawak tribes, including the Tainos, prior to the arrival of Columbus in 1494. Early inhabitants

of Jamaica named the land "Xaymaca", meaning "land of wood and water". The Spanish enslaved the Arawak,

who were ravaged further by diseases that the Spanish brought with them.

Early historians believe

that

by 1602, the Arawak-speaking Taino tribes were extinct. However, some of the Taino escaped into the

forested mountains of the interior, where they mixed with runaway African slaves, and survived free from

first Spanish, and then English, rule. The Spanish also captured and transported hundreds of West

African people to the island for the purpose of slavery. However, the majority of Africans were brought

into Jamaica by the English.

In 1655, the English invaded Jamaica, and defeated the Spanish. Some African enslaved people took

advantage of the political turmoil and escaped to the island's interior mountains, forming independent

communities which became known as the Maroons. Meanwhile, on the coast, the English built the settlement

of Port Royal, a base of operations where piracy flourished as so many European rebels had been rejected

from their countries to serve sentences on the seas. Captain Henry Morgan, a Welsh plantation owner and

privateer, raided settlements and shipping bases from Port Royal, earning him his reputation as one of

the richest pirates in the Caribbean.

In the 18th century, sugar cane replaced piracy as British Jamaica's main source of income. The sugar

industry was labour-intensive and the British brought hundreds of thousands of enslaved black Africans

to the island. By 1850, the black and mulatto Jamaican population outnumbered the white population by a

ratio of twenty to one. Enslaved Jamaicans mounted over a dozen major uprisings during the 18th century,

including Tacky's Revolt in 1760. There were also periodic skirmishes between the British and the

mountain communities of the Jamaican Maroons, culminating in the First Maroon War of the 1730s and the

Second Maroon War of 1795-1796. The aftermath of the Baptist War shone a light on the conditions of

slaves which contributed greatly to the abolition movement and the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act

1833, which formally ended slavery in Jamaica in 1834. However, relations between the white and black

community remained tense coming into the mid-19th century, with the most notable event being the Morant

Bay Rebellion in 1865.

The latter half of the 19th century saw economic decline, low crop prices, droughts, and disease. When

sugar lost its importance, many former plantations went bankrupt, and land was sold to Jamaican peasants

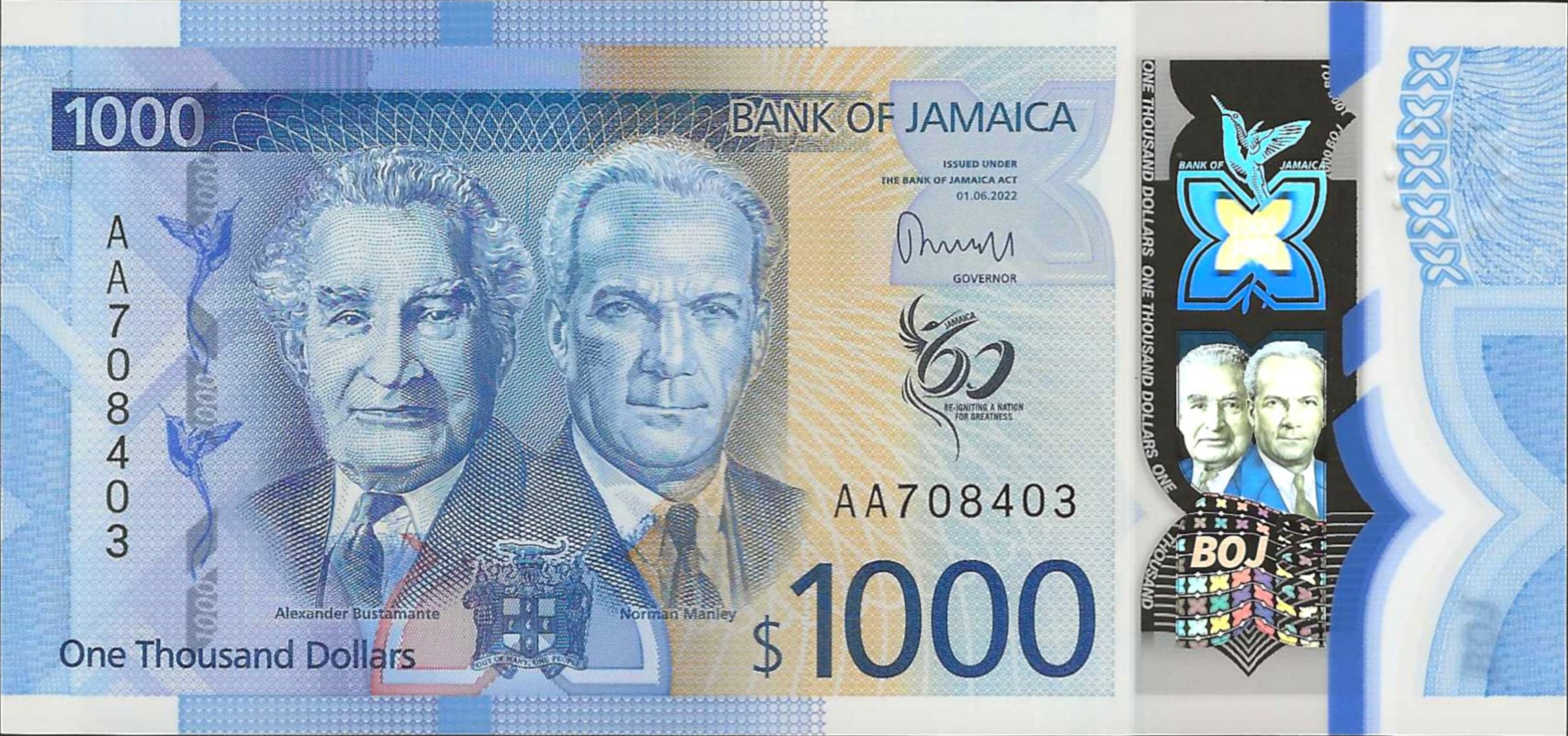

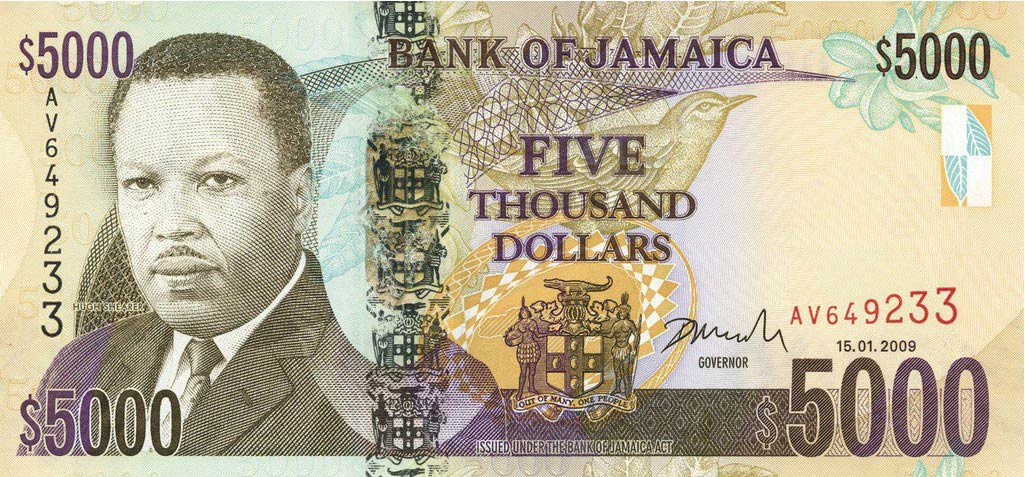

and cane fields were consolidated by dominant British producers. Jamaica's first political parties

emerged in the late 1920s, while workers association and trade unions emerged in the 1930s. The

development of a new Constitution in 1944, universal male suffrage, and limited self-government

eventually led to Jamaican Independence in 1962 with Alexander Bustamante serving as its first prime

minister. The country saw an extensive period of postwar growth and a smaller reliance on the

agricultural sector and a larger reliance on bauxite and mining in the 1960s and 1970s.

Political power changed hands between the two dominant parties, the JLP and PNP, from the 1970s to the

present day. While Jamaica's murder rate fell by nearly half after the 2010 Tivoli Incursion, the

country's murder rate remains one of the highest in the world. Economic troubles hit the country in

2013, the IMF agreed to a $1 billion loan to help Jamaica meet large debt payments, making Jamaica a

highly indebted country that spends around half of its annual budget on debt repayments. The first

inhabitants of Jamaica probably came from islands to the east in two waves of migration. About 600 CE

the culture known as the “Redware people” arrived. Little is known of these people, however, beyond the

red pottery they left behind. Alligator Pond in Manchester Parish and Little River in St. Ann Parish are

among the earliest known sites of this Ostionoid person, who lived near the coast and extensively hunted

turtles and fish. Around 800 CE, the Arawak tribes of the Tainos arrived, eventually settling throughout

the island. Living in villages ruled by tribal chiefs called the caciques, they sustained themselves on

fishing and the cultivation of maize and cassava.

At the height of their civilization, their population is estimated to have numbered as much as 60,000.

The Arawak brought a South America system of raising yuca known as "conuco" to the island. To add

nutrients to the soil, the Arawak burned local bushes and trees and heaped the ash into large mounds,

into which they then planted yuca cuttings. Most Arawak lived in large circular buildings (bohios),

constructed with wooden poles, woven straw, and palm leaves. The Arawak spoke an Arawakan language and

did not have writing. Some of the words used by them, such as barbacoa ("barbecue"), hamaca ("hammock"),

kanoa ("canoe"), tabaco ("tobacco"), yuca, batata ("sweet potato"), and juracán ("hurricane"), have been

incorporated When the English captured Jamaica in 1655, the Spanish colonists fled, leaving a large

number of African slaves. These former Spanish slaves organised under the leadership of rival captains

Juan de Serras and Juan de Bolas. These Jamaican Maroons intermarried with the Arawak people, and

established distinct independent communities in the mountainous interior of Jamaica.

They survived by subsistence farming and periodic raids of plantations. Over time, the Maroons came to

control large areas of the Jamaican interior. In the second half of the seventeenth century, de Serras

fought regular campaigns against English colonial forces, even attacking the capital of Spanish Town,

and he was never defeated by the English. Throughout the seventeenth century, and in the first few

decades of the eighteenth century, Maroon forces frequently defeated the British in small-scale

skirmishes. The British colonial authorities dispatched numerous expeditions in an attempt to subdue

them, but the Maroons successfully fought a guerrilla campaign against the British in the mountainous

interior, and forced the British government to seek peace terms to end the expensive conflict.

In the

early eighteenth century, English-speaking escaped Akan slaves were at the forefront of the Maroon

fighting against the British.

Tourism and

mining are the leading earners of foreign exchange. Half the

Jamaican economy relies on services, with half of its income coming from services such as tourism. An

estimated 4.3 million foreign tourists visit Jamaica every year.

Tourism and

mining are the leading earners of foreign exchange. Half the

Jamaican economy relies on services, with half of its income coming from services such as tourism. An

estimated 4.3 million foreign tourists visit Jamaica every year. Agricultural production is an important contributor to Jamaica's economy. However, it is vulnerable to

extreme weather, such as hurricanes and to competition from neighbouring countries such as the USA.

Other difficulties faced by farmers include thefts from the farm, known as praedial larceny.Agricultural

production accounted for 7.4% of GDP in 1997, providing employment for nearly a quarter of the country.

Agricultural production is an important contributor to Jamaica's economy. However, it is vulnerable to

extreme weather, such as hurricanes and to competition from neighbouring countries such as the USA.

Other difficulties faced by farmers include thefts from the farm, known as praedial larceny.Agricultural

production accounted for 7.4% of GDP in 1997, providing employment for nearly a quarter of the country.